2020年/01月/02日

HTDP第二版序

first edition of the book (1995–2000)

第一个版本过去了20年

spent fifteen years writing this edition

这个版本写了15年

Preface

Many professions require some form of programming. Accountants program spreadsheets; musicians program synthesizers; authors program word processors; and web designers program style sheets. When we wrote these words for the first edition of the book (1995–2000), readers may have considered them futuristic; by now, programming has become a required skill and numerous outlets—books, on-line courses, K-12 curricula—cater to this need, always with the goal of enhancing people’s job prospects.

许多职业需要某种形式的编程。会计师编程电子表格;音乐家编程声音合成器;作家编辑字处理器;网页设计师编程样式表。当我们为这本书的第一版 (1995-2000年) 写这些话的时候, 读者可能认为它们是未来主义的;到现在为止,编程已成为一项必要的技能,许多渠道–书籍、在线课程、k-12 课程–都能满足这一需要,其目标始终是提高人们的就业前景。

The typical course on programming teaches a “tinker until it works” approach. When it works, students exclaim “It works!” and move on. Sadly, this phrase is also the shortest lie in computing, and it has cost many people many hours of their lives. In contrast, this book focuses on habits of good programming, addressing both professional and vocational programmers.

典型的编程课程教授 “修补程序, 直到它工作” 的方法。当它能工作的时候,学生们惊呼 “跑起来了!” 然后继续前进。遗憾的是,这句话也是计算机中最短的谎言,它让许多人付出了数小时的生命代价。相反,这本书的重点是良好的编程习惯,针对的是专业和职业程序员。

By “good programming,” we mean an approach to the creation of software that relies on systematic thought, planning, and understanding from the very beginning, at every stage, and for every step. To emphasize the point, we speak of systematic program design and systematically designed programs. Critically, the latter articulates the rationale of the desired functionality. Good programming also satisfies an aesthetic sense of accomplishment; the elegance of a good program is comparable to time-tested poems or the black-and-white photographs of a bygone era. In short, programming differs from good programming like crayon sketches in a diner from oil paintings in a museum.

所谓 “好的编程”,我们指的是一种软件的创建方法,它从一开始、在每个阶段、在每一步都依赖于系统的思考、规划和理解。为了强调这一点,我们谈到了系统的程序设计和系统的设计程序。关键的是,后者阐明了所需功能的基本原理。好的编程也能满足审美成就感;一个好代码的优雅可以与久经考验的诗歌或过去时代的黑白照片相媲美。简而言之,代码和好代码之间的差别,就像餐馆里的蜡笔素描和博物馆里的油画之间的差别。

No, this book won’t turn anyone into a master painter. But, we would not have spent fifteen years writing this edition if we didn’t believe that

不, 这本书不会把任何人变成绘画大师。但是, 我们也不会花15年写这个版本, 如果我们不相信,

everyone can design programs

每个人都可以设计程序

and everyone can experience the satisfaction that comes with creative design.

每个人都可以体验到创意设计带来的满足。

Indeed, we go even further and argue that

program design—but not programming—deserves the same role in a liberal-arts education as mathematics and language skills.

事实上, 我们走得更远, 并认为

程序设计–而不是编程–应该在文科教育中扮演与数学和语言技能相同的角色。

A student of design who never touches a program again will still pick up universally useful problem-solving skills, experience a deeply creative activity, and learn to appreciate a new form of aesthetic. The rest of this preface explains in detail what we mean with “systematic design,” who benefits in what manner, and how we go about teaching it all.

一个学习了程序设计,并且之后再也不会接触编程的学生,仍然会获得普遍有用的解决问题的技能,依然会体验一个深刻的创造性活动,并学会欣赏一种新的审美形式。这个序言的其余部分详细解释了我们对 “系统设计” 的理解,谁以何种方式受益,以及我们如何去教授这一切。

Systematic Program Design

A program interacts with people, dubbed users, and other programs, in which case we speak of server and client components. Hence any reasonably complete program consists of many building blocks: some deal with input, some create output, while some bridge the gap between those two. We choose to use functions as fundamental building blocks because everyone encounters functions in pre-algebra and because the simplest programs are just such functions. The key is to discover which functions are needed, how to connect them, and how to build them from basic ingredients.

In this context, “systematic program design” refers to a mix of two concepts: design recipes and iterative refinement. The design recipes are a creation of the authors, and here they enable the use of the latter.

From Problem Analysis to Data Definitions

Identify the information that must be represented and how it is represented in the chosen programming language. Formulate data definitions and illustrate them with examples.

Signature, Purpose Statement, Header

State what kind of data the desired function consumes and produces. Formulate a concise answer to the question what the function computes. Define a stub that lives up to the signature.

Functional Examples

Work through examples that illustrate the function’s purpose.

Function Template

Translate the data definitions into an outline of the function.

Function Definition

Fill in the gaps in the function template. Exploit the purpose statement and the examples.

Testing

Articulate the examples as tests and ensure that the function passes all. Doing so discovers mistakes. Tests also supplement examples in that they help others read and understand the definition when the need arises—and it will arise for any serious program.

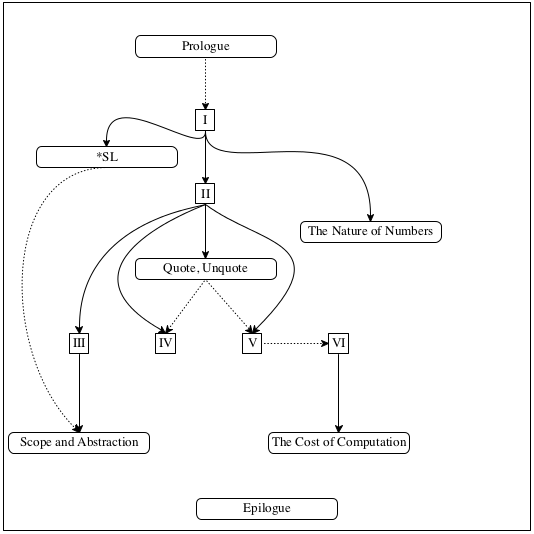

Figure 1: The basic steps of a function design recipe

Design Recipes apply to both complete programs and individual functions. This book deals with just two recipes for complete programs: one for programs with a graphical user interface (GUI) and one for batch programs. In contrast, design recipes for functions come in a wide variety of flavors: for atomic forms of data such as numbers; for enumerations of different kinds of data; for data that compounds other data in a fixed manner; for finite but arbitrarily large data; and so on.

The function-level design recipes share a common design process. Figure 1 displays its six essential steps. The title of each step specifies the expected outcome(s); the “commands” suggest the key activities. Examples play a central role at almost every stage.ask them to produce their card and point them to the step where they are stuck. For the chosen data representation in step 1, writing down examples proves how real-world information is encoded as data and how data is interpreted as information. Step 3 says that a problem-solver must work through concrete scenarios to gain an understanding of what the desired function is expected to compute for specific examples. This understanding is exploited in step 5, when it is time to define the function. Finally, step 6 demands that examples are turned into automated test code, which ensures that the function works properly for some cases. Running the function on real-world data may reveal other discrepancies between expectations and results.

Each step of the design process comes with pointed questions. For certain steps—say, the creation of the functional examples or the template—the questions may appeal to the data definition. The answers almost automatically create an intermediate product. This scaffolding pays off when it comes time to take the one creative step in the process: the completion of the function definition. And even then, help is available in almost all cases.

The novelty of this approach is the creation of intermediate products for beginner-level programs. When a novice is stuck, an expert or an instructor can inspect the existing intermediate products. The inspection is likely to use the generic questions from the design process and thus drive the novice to correct himself or herself. And this self-empowering process is the key difference between programming and program design.

Iterative Refinement addresses the issue that problems are complex and multifaceted. Getting everything right at once is nearly impossible. Instead, computer scientists borrow iterative refinement from the physical sciences to tackle this design problem. In essence, iterative refinement recommends stripping away all inessential details at first and finding a solution for the remaining core problem. A refinement step adds in one of these omitted details and re-solves the expanded problem, using the existing solution as much as possible. A repetition, also called an iteration, of these refinement steps eventually leads to a complete solution.

In this sense, a programmer is a miniscientist. Scientists create approximate models for some idealized version of the world to make predictions about it. As long as the model’s predictions come true, everything is fine; when the predicted events differ from the actual ones, scientists revise their models to reduce the discrepancy. In a similar vein, when programmers are given a task, they create a first design, turn it into code, evaluate it with actual users, and iteratively refine the design until the program’s behavior closely matches the desired product.

This book introduces iterative refinement in two different ways. Since designing via refinement becomes useful even when the design of programs becomes complex, the book introduces the technique explicitly in the fourth part, once the problems acquire a certain degree of difficulty. Furthermore, we use iterative refinement to state increasingly complex variants of the same problem over the course of the first three parts of the book. That is, we pick a core problem, deal with it in one chapter, and then pose a similar problem in a subsequent chapter—with details matching the newly introduced concepts.

系统程序设计

程序与人交互,我们称对方是用户;程序和其他程序交互, 我们把他们称作服务器组件和客户端组件。因此, 任何合理完整的程序都由许多构建块构成:一些处理输入, 一些创建输出,而一些则弥合这两个组成部分之间的差距。我们选择使用函数作为基本的构建块, 因为每个人都会在初级代数中遇到函数,而且最简单的程序就是一个函数。关键是要发现哪些函数是需要的,如何连接它们,以及如何用基本的佐料去构建它们。

在这种语境下,”系统程序设计” 混合了两个概念: 设计配方和迭代优化。

函数设计配方的基本步骤

1、从问题分析到数据定义

确定必须要表达的信息,以及在特定的程序语言中该如何表达。 制定数据定义并用示例说明它们。

2、签名,意图声明,标题

用来表述函数生产者和消费者的数据状态。为函数计算的问题制定一个简明的答案。 定义符合签名的存根。

3、功能性的例子

通过例子来表示函数的意图

4、函数模板

将数据定义转换为函数的大纲。

5、函数定义

填满函数模板中的空白。 利用意图描述和示例。

6、测试

把示例当成测试并确保函数通过所有示例。 这样做可以发现错误。 测试还补充了一些例子,它们可以帮助其他人在需要时阅读和理解函数 - 并且把它用在其他严肃的程序中。

设计配方适用于完整程序和单个功能。 本书仅涉及完整程序的两个配方:一个用于具有图形用户界面(GUI)的程序,另一个用于批处理程序。 相比之下,功能的设计配方有各种各样的风格:数据的原子形式,如数字; 列举不同类型的数据; 用于以固定方式合成其他数据的数据; 对于有限但任意大的数据; 等等。

功能级设计配方共享一个共同的设计过程。 图1显示了其六个基本步骤。 每个步骤的标题指定了预期的结果; “命令”表明了关键活动。 示例几乎在每个阶段都发挥着核心作用。 对于步骤1中选择的数据表示,写下示例证明了如何将现实世界信息编码为数据以及如何将数据解释为信息。 第3步说明问题解决者必须通过具体方案来了解特定示例所期望的功能。 当需要定义函数时,在步骤5中利用这种理解。 最后,步骤6要求将示例转换为自动化测试代码,以确保该功能在某些情况下正常工作。 在真实世界数据上运行该功能可能会揭示期望和结果之间的其他差异。

设计过程的每一步都有尖锐的问题。 对于某些步骤 - 比如功能性示例或模板的创建 - 问题可能会吸引数据定义。 答案几乎自动创建一个中间产品。 当需要在流程中采取一个创造性步骤时,这个脚手架会得到回报:功能定义的完成。 即便如此,几乎在所有情况下都可以获得帮助。

这种方法的新颖之处在于为初级程序创建中间产品。 当新手卡住时,专家或讲师可以检查现有的中间产品。 检查可能会使用设计过程中的一般性问题,从而促使新手纠正自己。 而这种自我赋权过程是编程和程序设计之间的关键区别。

迭代细化解决了问题复杂多面的问题。一下子完成所有事情几乎是不可能的。相反,计算机科学家借用物理科学的迭代改进来解决这个设计问题。本质上,迭代细化建议首先剥离所有不必要的细节,并找到剩余核心问题的解决方案。细化步骤添加了其中一个省略的细节,并尽可能使用现有解决方案重新解决扩展的问题。这些细化步骤的重复(也称为迭代)最终导致完整的解决方案。

从这个意义上说,程序员是一个小型科学家。科学家为一些理想化的世界版本创建近似模型,以对其进行预测。只要模型的预测成真,一切都很好;当预测的事件与实际事件不同时,科学家会修改他们的模型以减少差异。类似地,当程序员被赋予任务时,他们创建第一个设计,将其转换为代码,用实际用户对其进行评估,并迭代地改进设计,直到程序的行为与所需产品紧密匹配。

本书以两种不同的方式介绍了迭代细化。由于即使在程序设计变得复杂时,通过细化设计也变得有用,因此一旦问题获得一定程度的困难,本书将在第四部分中明确地介绍该技术。此外,在本书前三部分的过程中,我们使用迭代细化来陈述同一问题的日益复杂的变体。也就是说,我们选择一个核心问题,在一章中处理它,然后在后续章节中提出类似的问题 - 细节与新引入的概念相匹配。

DrRacket and the Teaching Languages

Learning to design programs calls for repeated hands-on practice. Just as nobody becomes a piano player without playing the piano, nobody becomes a program designer without creating actual programs and getting them to work properly. Hence, our book comes with a modicum of software support: a language in which to write down programs and a program development environment with which programs are edited like word documents and with which readers can run programs.

Many people we encounter tell us they wish they knew how to code and then ask which programming language they should learn. Given the press that some programming languages get, this question is not surprising. But it is also wholly inappropriate. Learning to program in a currently fashionable programming language often sets up students for eventual failure. Fashion in this world is extremely short lived. A typical “quick programming in X” book or course fails to teach principles that transfer to the next fashion language. Worse, the language itself often distracts from the acquisition of transferable skills, at the level of both expressing solutions and dealing with programming mistakes.

In contrast, learning to design programs is primarily about the study of principles and the acquisition of transferable skills. The ideal programming language must support these two goals, but no off-the-shelf industrial language does so. The crucial problem is that beginners make mistakes before they know much of the language, yet programming languages always diagnose these errors as if the programmer already knew the whole language. As a result, diagnosis reports often stump beginners.

Our solution is to start with our own tailor-made teaching language, dubbed “Beginning Student Language” or BSL. The language is essentially the “foreign” language that students acquire in pre-algebra courses. It includes notation for function definitions, function applications, and conditional expressions. Also, expressions can be nested. This language is thus so small that an error diagnosis in terms of the whole language is still accessible to readers with nothing but pre-algebra under their belt.

A student who has mastered the structural design principles can then move on to “Intermediate Student Language” and other advanced dialects, collectively dubbed *SL. The book uses these dialects to teach design principles of abstraction and general recursion. We firmly believe that using such a series of teaching languages provides readers with a superior preparation for creating programs for the wide spectrum of professional programming languages (JavaScript, Python, Ruby, Java, and others).

Note The teaching languages are implemented in Racket, a programming language we built for building programming languages. Racket has escaped from the lab into the real world, and it is a programming vehicle of choice in a variety of settings, from gaming to the control of telescope arrays. Although the teaching languages borrow elements from the Racket language, this book does not teach Racket. Then again, a student who has completed this book can easily move on to Racket. End

When it comes to programming environments, we face an equally bad choice as the one for languages. A programming environment for professionals is analogous to the cockpit of a jumbo jet. It has numerous controls and displays, overwhelming anyone who first launches such a software application. Novice programmers need the equivalent of a two-seat, single-engine propeller aircraft with which they can practice basic skills. We have therefore created DrRacket, a programming environment for novices.

DrRacket supports highly playful, feedback-oriented learning with just two simple interactive panes: a definitions area, which contains function definitions, and an interactions area, which allows a programmer to ask for the evaluation of expressions that may refer to the definitions. In this context, it is as easy to explore “what if” scenarios as in a spreadsheet application. Experimentation can start on first contact, using conventional calculator-style examples and quickly proceeding to calculations with images, words, and other forms of data.

An interactive program development environment such as DrRacket simplifies the learning process in two ways. First, it enables novice programmers to manipulate data directly. Because no facilities for reading input information from files or devices are needed, novices don’t need to spend valuable time on figuring out how these work. Second, the arrangement strictly separates data and data manipulation from input and output of information from the “real world.” Nowadays this separation is considered so fundamental to the systematic design of software that it has its own name: model-view-controller architecture. By working in DrRacket, new programmers are exposed to this fundamental software engineering idea in a natural way from the get-go.

DrRacket和教学语言

学习设计课程需要反复练习练习。 正如没有人在没有弹钢琴的情况下成为钢琴演奏者一样,没有人成为程序设计师而没有创建实际的程序并让他们正常工作。 因此,我们的书中提供了一些软件支持:一种用于记下程序的语言和一种程序开发环境,用于编写程序,如word文档和读者可以运行程序。

我们遇到的很多人告诉我们他们希望他们知道如何编码,然后询问他们应该学习哪种编程语言。 鉴于某些编程语言的新闻,这个问题并不令人惊讶。 但这也完全不合适。 学习使用当前流行的编程语言进行编程通常会使学生最终失败。 这个世界的时尚极短暂。 典型的“X中的快速编程”一书或课程无法教授转移到下一种时尚语言的原则。 更糟糕的是,在表达解决方案和处理编程错误的层面上,语言本身往往会分散对可转移技能的获取。

相比之下,学习设计课程主要是关于原则的研究和可转移技能的获得。 理想的编程语言必须支持这两个目标,但没有现成的工业语言。 关键问题是初学者在了解大部分语言之前会犯错误,但编程语言总是会诊断出这些错误,好像程序员已经知道整个语言一样。 因此,诊断报告通常会使初学者陷入困境。

我们的解决方案是从我们自己量身定制的教学语言开始,称为“初学者语言”或BSL。 该语言本质上是学生在预代数课程中获得的“外语”语言。 它包括函数定义,函数应用程序和条件表达式的表示法。 此外,表达式可以被证实。 因此,这种语言是如此之小,以至于读者仍然可以获得整个语言的错误诊断,除了他们之前的代数之外什么都没有。

已经掌握了结构设计原则的学生可以转到“中级学生语言”和其他高级方言,统称为* SL。 本书使用这些方言来教授抽象和一般递归的设计原则。 我们坚信,使用这样一系列教学语言为读者提供了为各种专业编程语言(JavaScript,Python,Ruby,Java等)创建程序的卓越准备。

教学语言是在Racket中实现的,这是我们为构建编程语言而构建的编程语言。 Racket已从实验室逃到现实世界,它是各种设置中的编程工具,从游戏到望远镜阵列的控制。 虽然教学语言借用了Racket语言中的元素,但本书并没有教授Racket。 然后,完成本书的学生可以轻松转到Racket。

在编程环境方面,我们面临着与语言一样糟糕的选择。专业人士的编程环境类似于大型喷气式飞机的驾驶舱。它有许多控件和显示器,压倒了首次启动这样一个软件应用程序的人。新手程序员需要相当于双座单引擎螺旋桨飞机,他们可以用它们练习基本技能。因此,我们创建了DrRacket,一个面向新手的编程环境。

DrRacket只用两个简单的交互式窗格支持高度有趣,反馈导向的学习:定义区域,包含函数定义,以及交互区域,允许程序员请求评估可能引用定义的表达式。在这种情况下,可以像在电子表格应用程序中一样轻松地探索“假设”场景。实验可以在第一次接触时开始,使用传统的计算器式示例,并快速进行图像,文字和其他形式的数据计算。

DrRacket等交互式程序开发环境以两种方式简化了学习过程。首先,它使新手程序员能够直接操作数据。因为不需要用于从文件或设备读取输入信息的设施,所以新手不需要花费宝贵的时间来弄清楚这些是如何工作的。其次,这种安排严格地将数据和数据操作与来自“现实世界”的信息的输入和输出分开。现在,这种分离被认为是软件系统设计的基础,它有自己的名称:模型 - 视图 - 控制器架构。通过在DrRacket工作,新程序员从一开始就以自然的方式接触这种基本的软件工程理念。

Skills that Transfer

The skills acquired from learning to design programs systematically transfer in two directions. Naturally, they apply to programming in general as well as to programming spreadsheets, synthesizers, style sheets, and even word processors. Our observations suggest that the design process from figure 1 carries over to almost any programming language, and it works for 10-line programs as well as for 10,000-line programs. It takes some reflection to adopt the design process across the spectrum of languages and scale of programming problems; but once the process becomes second nature, its use pays off in many ways.

Learning to design programs also means acquiring two kinds of universally useful skills. Program design certainly teaches the same analytical skills as mathematics, especially (pre)algebra and geometry. But, unlike mathematics, working with programs is an active approach to learning. Creating software provides immediate feedback and thus leads to exploration, experimentation, and self-evaluation. The results tend to be interactive products, an approach that vastly increases the sense of accomplishment when compared to drill exercises in textbooks.

In addition to enhancing a student’s mathematical skills, program design teaches analytical reading and writing skills. Even the smallest design tasks are formulated as word problems. Without solid reading and comprehension skills, it is impossible to design programs that solve a reasonably complex problem. Conversely, program design methods force a creator to articulate his or her thoughts in proper and precise language. Indeed, if students truly absorb the design recipe, they enhance their articulation skills more than anything else.

To illustrate this point, take a second look at the process description in figure 1. It says that a designer must analyze a problem statement, typically stated as a word problem;

extract and express its essence, abstractly;

illustrate the essence with examples;

make outlines and plans based on this analysis;

evaluate results with respect to expected outcomes; and

revise the product in light of failed checks and tests.

Each step requires analysis, precision, description, focus, and attention to details. Any experienced entrepreneur, engineer, journalist, lawyer, scientist, or any other professional can explain how many of these skills are necessary for his or her daily work. Practicing program design—on paper and in DrRacket—is a joyful way to acquire these skills.

Similarly, refining designs is not restricted to computer science and program creation. Architects, composers, writers, and other professionals do it, too. They start with ideas in their head and somehow articulate their essence. They refine these ideas on paper until their product reflects their mental image as much as possible. As they bring their ideas to paper, they employ skills analogous to fully absorbed design recipes: drawing, writing, or piano playing to express certain style elements of a building, describe a person’s character, or formulate portions of a melody. What makes them productive with an iterative development process is that they have absorbed their basic design recipes and learned how to choose which one to use for the current situation.

技能和转移

从学习到设计程序所获得的技能系统地向两个方向转移。当然,它们适用于编程,以及编程电子表格,合成器,样式表甚至文字处理器。我们的观察表明,图1中的设计过程几乎可以用于任何编程语言,它适用于10行程序以及10,000行程序。在整个语言范围和编程问题规模上采用设计过程需要一些反思;但是一旦这个过程成为第二天性,它的使用会在很多方面得到回报。

学习设计课程也意味着获得两种普遍有用的技能。程序设计当然教授与数学相同的分析技能,特别是(预)代数和几何。但是,与数学不同,使用程序是一种积极的学习方法。创建软件可提供即时反馈,从而进行探索,实验和自我评估。结果往往是互动产品,与教科书中的练习相比,这种方法大大增加了成就感。

除了提高学生的数学技能外,课程设计还教授分析性阅读和写作技巧。即使是最小的设计任务也被制定为单词问题。如果没有扎实的阅读和理解技巧,就不可能设计出解决相当复杂问题的程序。相反,程序设计方法迫使创作者用恰当和精确的语言表达他或她的思想。事实上,如果学生真正吸收设计配方,他们就会比其他任何事情更能提高他们的发音技巧。

为了说明这一点,请再看一下图1中的过程描述。它说设计师必须这样做

分析问题陈述,通常表示为单词问题;

抽象地提取并表达其本质;

用例子说明了本质;

根据此分析制定大纲和计划;

评估预期结果的结果;和

根据检查和测试失败修改产品。

每个步骤都需要分析,精确度,描述,重点和对细节的关注。任何经验丰富的企业家,工程师,记者,律师,科学家或任何其他专业人士都可以解释这些技能中有多少是他们日常工作所必需的。练习程序设计 - 在纸上和DrRacket中 - 是获得这些技能的快乐方式。

同样,精炼设计不仅限于计算机科学和程序创建。建筑师,作曲家,作家和其他专业人士也这样做。他们从头脑中的想法开始,并以某种方式表达他们的本质。他们在纸上改进这些想法,直到他们的产品尽可能地反映他们的心理形象。当他们将自己的想法带到纸上时,他们会采用类似于完全吸收的设计方法的技巧:绘画,书写或钢琴演奏来表达建筑物的某些风格元素,描述一个人的角色,或者制定旋律的一部分。通过迭代开发过程使他们富有成效的原因是他们已经吸收了他们的基本设计配方,并学会了如何选择当前使用的配方。

This Book and Its Parts

The purpose of this book is to introduce readers without prior experience to the systematic design of programs. In tandem, it presents a symbolic view of computation, a method that explains how the application of a program to data works. Roughly speaking, this method generalizes what students learn in elementary school arithmetic and middle school algebra. But have no fear. DrRacket comes with a mechanism—the algebraic stepper—that can illustrate these step-by-step calculations.

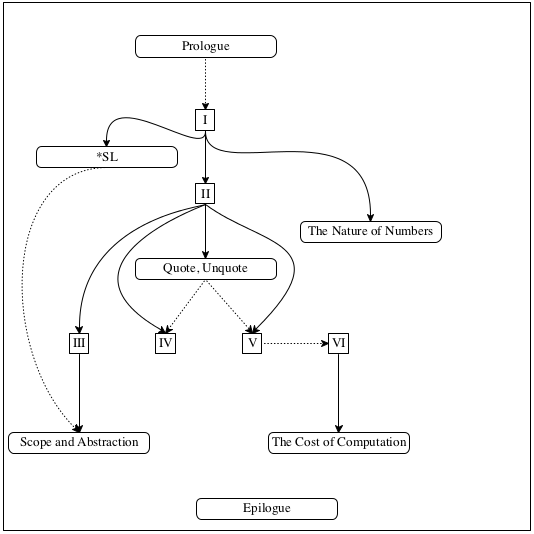

The book consists of six parts separated by five intermezzos and is bookended by a Prologue and an Epilogue. While the major parts focus on program design, the intermezzos introduce supplementary concepts concerning programming mechanics and computing.

Prologue: How to Program is a quick introduction to plain programming. It explains how to write a simple animation in *SL. Once finished, any beginner is bound to feel simultaneously empowered and overwhelmed. The final note therefore explains why plain programming is wrong and how a systematic, gradual approach to program design eliminates the sense of dread that every beginning programmer usually experiences. Now the stage is set for the core of the book: Fixed-Size Data explains the most fundamental concepts of systematic design using simple examples. The central idea is that designers typically have a rough idea of what data the program is supposed to consume and produce. A systematic approach to design must therefore extract as many hints as possible from the description of the data that flows into and out of a program. To keep things simple, this part starts with atomic data—numbers, images, and so on—and then gradually introduces new ways of describing data: intervals, enumerations, itemizations, structures, and combinations of these.

Intermezzo 1: Beginning Student Language describes the teaching language in complete detail: its vocabulary, its grammar, and its meaning. Computer scientists refer to these as syntax and semantics. Program designers use this model of computation to predict what their creations compute when run or to analyze error diagnostics.

Arbitrarily Large Data extends Fixed-Size Data with the means to describe the most interesting and useful forms of data: arbitrarily large compound data. While a programmer may nest the kinds of data from Fixed-Size Data to represent information, the nesting is always of a fixed depth and breadth. This part shows how a subtle generalization gets us from there to data of arbitrary size. The focus then switches to the systematic design of programs that process this kind of data.

Intermezzo 2: Quote, Unquote introduces a concise and powerful notation for writing down large pieces of data: quotation and anti-quotation.

Abstraction acknowledges that many of the functions from Arbitrarily Large Data look alike. No programming language should force programmers to create pieces of code that are so similar to each other. Conversely, every good programming language comes with ways to eliminate such similarities. Computer scientists call both the step of eliminating similarities and its result abstraction, and they know that abstractions greatly increase a programmer’s productivity. Hence, this part introduces design recipes for creating and using abstractions.

Intermezzo 3: Scope and Abstraction plays two roles. On the one hand, it injects the concept of lexical scope, the idea that a programming language ties every occurrence of a name to a definition that a programmer can find with an inspection of the code. On the other hand, it explains a library with additional mechanisms for abstraction, including so-called for loops.

Intertwined Data generalizes Arbitrarily Large Data and explicitly introduces the idea of iterative refinement into the catalog of design concepts.

Intermezzo 4: The Nature of Numbers explains and illustrates why decimal numbers work in such strange ways in all programming languages. Every budding programmer ought to know these basic facts.

Generative Recursion adds a new design principle. While structural design and abstraction suffice for most problems that programmers encounter, they occasionally lead to insufficiently “performant” programs. That is, structurally designed programs might need too much time or energy to compute the desired answers. Computer scientists therefore replace structurally designed programs with programs that benefit from ad hoc insights into the problem domain. This part of the book shows how to design a large class of just such programs.

Intermezzo 5: The Cost of Computation uses examples from Generative Recursion to illustrate how computer scientists think about performance.

Accumulators adds one final trick to the toolbox of designers: accumulators. Roughly speaking, an accumulator adds “memory” to a function. The addition of memory greatly improves the performance of structurally designed functions from the first four parts of the book. For the ad hoc programs from Generative Recursion, accumulators can make the difference between finding an answer and never finding one.

Epilogue: Moving On is both an assessment and a look ahead to what’s next.

Independent readers ought to work through the entire book, from the first page to the last. We say “work” because we really mean that a reader ought to solve all exercises or at least know how to solve them.

Similarly, instructors ought to cover as many elements as possible, starting from the Prologue all the way through the Epilogue. Our teaching experience suggests that this is doable. Typically, we organize our courses so that our readers create a sizable and entertaining program over the course of the semester. We understand, however, that some circumstances call for significant cuts and that some instructors’ tastes call for slightly different ways to use the book.

Figure 2 is a navigation chart for those who wish to pick and choose from the elements of the book. The figure is a dependency graph. A solid arrow from one element to another suggests a mandatory ordering; for example, Part II requires an understanding of Part I. In contrast, a dotted arrow is mostly a suggestion; for example, understanding the Prologue is unnecessary to get through the rest of the book.

Based on this chart, here are three feasible paths through the book: A high school instructor may want to cover (as much as possible of) parts I and II, including a small project such as a game.

A college instructor in a quarter system may wish to focus on Fixed-Size Data, Arbitrarily Large Data, Abstraction, and Generative Recursion, plus the intermezzos on *SL and scope.

A college instructor in a semester system may prefer to discuss performance trade-offs in designs as early as possible. In this case, it is best to cover Fixed-Size Data and Arbitrarily Large Data and then the accumulator material from Accumulators that does not depend on Generative Recursion. At that point, it is possible to discuss Intermezzo 5: The Cost of Computation and to study the rest of the book from this angle.

Iteration of Sample Topics The book revisits certain exercise and sample topics time and again. For example, virtual pets are found all over Fixed-Size Data and even show up in Arbitrarily Large Data. Similarly, both Fixed-Size Data and Arbitrarily Large Data cover alternative approaches to implementing an interactive text editor. Graphs appear in Generative Recursion and immediately again in Accumulators. The purpose of these iterations is to motivate iterative refinement and to introduce it through the backdoor. We urge instructors to assign these themed sequences of exercises or to create their own such sequences.

本书和章节

本书的目的是向没有经验的读者介绍程序的系统设计。同时,它提供了一种计算的符号视图,这种方法解释了程序应用程序如何工作。粗略地说,这种方法概括了学生在小学算术和中学代数中学到的东西。但不要害怕。 DrRacket带有一种机制 - 代数步进器 - 可以说明这些逐步计算。

这本书由六个部分组成,由五个幕间剧分隔,并由序言和一个结语组织在一起。虽然主要部分侧重于程序设计,但幕间剧引入了有关编程机制和计算的补充概念。

序言:如何编程 是对直白编程的快速介绍。它解释了如何在*SL中编写一个简单的动画。一旦完成,任何初学者一定会同时感到强大和不知所措。因此,最后的注释解释了为什么直白编程是错误的,以及一个系统的、渐进的程序设计方法是如何消除每个初学者通常经历的恐惧感。现在,来介绍本书的核心部分:

固定大小的数据 使用简单的例子解释了系统设计的最基本概念。中心思想是设计人员通常会有一个大致的想法,程序中的核心数据,是如何产生和消费的。因此,系统的设计方法必须从流入和流出程序的数据描述中提取尽可能多的提示。为了简单起见,这部分从原子数据 - 数字,图像等开始 - 然后逐步引入描述数据的新方法:间隔,枚举,分项,结构,以及这些的组合。

幕间剧 1:初级学生语言 详细地描述了教学语言:它的词汇、语法和意义。计算机科学家称之为语法和语义。程序设计人员使用这种计算模型来预测他们的创造物在运行时计算的内容或分析错误诊断。

任意大数据扩展了固定大小的数据,可以用来描述最有趣和最有用的数据形式:任意大的复合数据。虽然程序员可以从固定大小的数据中嵌套数据来表示信息,但是嵌套的深度和宽度总是固定的。这一部分展示了一个微妙的概括是如何将我们从这里带到任意大小的数据的。然后重点转向处理这类数据的程序的系统设计。

幕间剧 2:引用,引用结束 为写大量数据引入了简洁而强大的符号:引用和反引号。

抽象承认任意大数据的许多函数看起来很相似。任何编程语言都不应该强迫程序员创建彼此如此相似的代码片段。相反,每一种好的编程语言都有消除这种相似性的方法。计算机科学家将消除相似性的步骤和结果抽象都称为消除相似性的步骤,他们知道抽象极大地提高了程序员的生产力。因此,本部分介绍了创建和使用抽象的设计方法。

幕间剧 3:作用域和抽象扮演两个角色。一方面,它注入了词法作用域的概念,即编程语言将名称的每次出现都与程序员通过检查代码可以找到的定义联系起来。另一方面,它解释了一个具有额外抽象机制的库,包括所谓的for循环。

相互交织的数据概括任意大的数据,并在设计概念的目录中明确地引入迭代细化的思想。

幕间剧 4:数字的本质解释和说明了为什么十进制数字在所有编程语言中都以如此奇怪的方式工作。每个初出茅庐的程序员都应该知道这些基本事实。

生成递归增加了新的设计原则。虽然结构设计和抽象对于程序员遇到的大多数问题来说已经足够了,但是它们偶尔会导致“性能”不足的程序。也就是说,结构设计的程序可能需要太多的时间或精力来计算所需的答案。因此,计算机科学家将结构设计的程序替换为从对问题领域的特别洞察中获益的程序。本书的这一部分展示了如何设计这样一个大型类的程序。

幕间剧 5:计算成本使用生成递归的例子来说明计算机科学家如何看待性能。

累加器为设计器工具箱增加了最后一个技巧:累加器。粗略地说,累加器向函数添加“内存”。从本书的前四部分开始,内存的添加大大提高了结构设计函数的性能。对于生成递归中的特殊程序,累加器可以决定是否找到答案。

结语:继续前进既是一种评估,也是对未来的展望。

独立读者应该通读整本书,从第一页到最后一页。我们说“工作”是因为我们真正的意思是读者应该解决所有的练习或至少知道如何解决它们。

同样的,导师应该尽可能多地涵盖元素,从前言一直到结语。我们的教学经验表明这是可行的。通常,我们组织我们的课程,以便我们的读者在本学期的课程中创建一个规模庞大的娱乐节目。然而,我们明白,在某些情况下需要大幅削减开支,而一些教师的口味则要求以略微不同的方式使用这本书。

下图是一个导航图,供那些希望从书中的元素中进行选择的人使用。图是一个依赖关系图。从一个元素到另一个元素的实箭头表示强制排序;例如,第二部分要求理解第一部分。相比之下,虚线箭头主要是一个建议;例如,理解序言对于读完本书的其余部分是不必要的。

根据这张图表,本书有三条可行的路径:

高中教师可能想要涵盖(尽可能多的)第一部分和第二部分,包括一个小项目,如游戏。 四分之一系统中的大学讲师可能希望专注于固定大小的数据、任意大的数据、抽象和生成递归,以及*SL和作用域。 一个学期制的大学讲师可能更喜欢尽早讨论设计中的性能权衡。在这种情况下,最好覆盖固定大小的数据和任意大的数据,然后是累加器,不依赖生成递归。在这一点上,有可能讨论幕间剧5:计算成本,并从这个角度研究本书的其余部分。 示例的迭代 本书一次又一次地回顾某些练习和示例。例如,虚拟宠物在固定大小的数据中随处可见,甚至出现在任意大的数据中。类似地,固定大小的数据和任意大的数据都涵盖了实现交互式文本编辑器的其他方法。图以生成递归的形式出现,并立即以累加器的形式再次出现。这些迭代的目的是激发迭代细化并通过后门引入它。我们敦促教师分配这些主题序列的练习或创建自己的序列。

The Differences

This second edition of How to Design Programs differs from the first one in several major aspects: It explicitly acknowledges the difference between designing a whole program and the functions that make up a program. Specifically, this edition focuses on two kinds of programs: event-driven (mostly GUI, but also networking) programs and batch programs.

The design of a program proceeds in a top-down planning phase followed by a bottom-up construction phase. We explicitly show how the interface to libraries dictates the shape of certain program elements. In particular, the very first phase of a program design yields a wish list of functions. While the concept of a wish list exists in the first edition, this second edition treats it as an explicit design element.

Fulfilling an entry from the wish list relies on the function design recipe, which is the subject of the six major parts.

A key element of structural design is the definition of functions that compose others. This design-by-composition is especially useful for the world of batch programs. Like generative recursion,We thank Kathi Fisler for calling our attention to this point. it requires a eureka!, specifically a recognition that the creation of intermediate data by one function and processing this intermediate result by a second function simplifies the overall design. This approach also needs a wish list, but formulating these wishes calls for an insightful development of an intermediate data definition. This edition of the book weaves in a number of explicit exercises on design by composition.

While testing has always been a part of our design philosophy, the teaching languages and DrRacket started supporting it properly only in 2002, just after we had released the first edition. This new edition heavily relies on this testing support.

This edition of the book drops the design of imperative programs. The old chapters remain available on-line. An adaptation of this material will appear in the second volume of this series, How to Design Components.

The book’s examples and exercises employ new teachpacks. The preferred style is to link in these libraries via require, but it is still possible to add teachpacks via a menu in DrRacket.

Finally, this second edition differs from the first in a few aspects of terminology and notation:

Second Edition First Edition

signature contract

itemization union

'() empty

#true true

#false false

The last three differences greatly improve quotation for lists.

和第一版的差异

第二版《如何设计程序》在几个主要方面与第一版有所不同:

它明确承认设计整个程序和组成程序的函数之间的区别。具体来说,这个版本主要关注两种程序:事件驱动程序(主要是GUI,但也包括网络)和批处理程序。 程序的设计在自顶向下的计划阶段和自底向上的构建阶段中进行。我们显式地展示了库的接口如何指定某些程序元素的形状。特别地,程序设计的第一个阶段会产生一个期望的函数列表。虽然愿望列表的概念存在于第一版中,但第二版将其视为显式设计元素。 实现愿望列表中的条目依赖于功能设计配方,这是六个主要部分的主题。 结构设计的一个关键元素是定义组成其他函数的函数。这种按组合方式设计的方法对于批处理程序尤其有用。就像生成递归一样,它需要一个eureka!,特别是认识到由一个函数创建中间数据并由第二个函数处理这个中间结果简化了总体设计。这种方法还需要一个愿望列表,但是制定这些愿望需要对中间数据定义进行深入的开发。这本书的这个版本编织了一些明确的练习设计的组成。 虽然测试一直是我们设计理念的一部分,但教学语言和DrRacket直到2002年才开始适当地支持它,当时我们刚刚发布了第一版。这个新版本很大程度上依赖于这种测试支持。 这本书的这个版本省略了命令式程序的设计。旧的章节仍然可以在网上找到。本系列的第二册《如何设计组件》将介绍对这种材料的改编。 书中的例子和练习采用了新的教学包。首选的样式是通过require链接到这些库中,但是仍然可以通过DrRacket中的菜单添加教学包。 最后,第二版与第一版在一些术语和符号方面有所不同:

Second Edition First Edition

signature contract

itemization union

'() empty

#true true

#false false